These two things fight together in me as the snakes fight in the spring. The water comes out of my eyes; but I laugh while it falls. Why?

–Mowgli in The Jungle Book

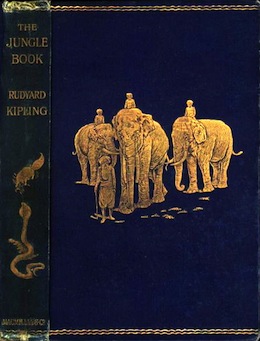

Unlike most of the other works covered in this Read-Watch, Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book is not one work or story, but rather a collection of short stories and poems first published in the late 19th century. The first half of the book contains stories about Mowgli, a young boy raised by wolves, a bear and a panther in the jungle, and his great enemy Shere Khan the Tiger. The second, better half of the book tells tales about a fur seal searching for an island free from hunters; a fighting mongoose; a young boy who witnesses an elephant dance; and a story that involves a lot of horses complaining about their riders. Only two things connect the stories: all of them include animals, and all focus on the struggle to find a place to belong.

Rudyard Kipling was very familiar with that theme. Born in India to British parents, he was sent to Britain when he was only five, an experience he remembered with misery for the rest of his life. He did not do well in school, so his parents recalled him to British India at the age of 16, finding him a job in Lahore, now in Pakistan. Just seven years later, he found himself heading back to London, and then to the United States, then back to London, and then to Vermont, before returning again to England. It was not quite a rootless life—the adult Kipling found houses and homes—but Kipling was never to feel himself entirely English, or, for that matter, entirely Anglo-Indian, and certainly not American, though later critics were to firmly label him as imperialist, and definitely British. Having Conservative British prime minister Stanley Baldwin as a cousin helped that label stick.

That seeming rootlessness drove much of his writing, something he was virtually addicted to. From his return to India until his death in 1936 at the age of 70, Kipling wrote almost constantly. He won the Nobel Prize in 1907 for his often controversial novels and poems (most notably “White Man’s Burden,” which has alternatively been read as pure propaganda or satire). The stories in The Jungle Book were largely written in Vermont, with Kipling reaching back to his past for inspiration, and they have, at times, almost a nostalgic feel.

I’ll confess it right now: I’ve always found it difficult to get into The Jungle Book, and this reread was no different. Part of the problem might be the thees and thous that litter the first part of the book: this tends to be something I have little patience with in more modern books (that is, the 19th century and onwards) unless the text provides good reason for it, and “Talking animals” doesn’t seem like a particularly good reason. (I came to this book after Oz, Narnia, and Wonderland had introduced me to the idea that animals could talk, even if they usually did so in other worlds, not ours.) As proof of that, I’ll note that the thees and thous used in the final story, “Toomai of the Elephants,” for instance, are somehow a little less annoying because they are voiced by humans. But they are still mildly annoying.

I also find myself flinching at this:

So Mowgli went away and hunted with the four cubs in the jungle from that day on. But he was not always alone, because, years afterwards, he became a man and married.

But that is a story for grown-ups.

First, Kipling, of course Mowgli wasn’t alone—you just told us that he was with four wolf cubs who could speak, if, admittedly, only with a lot of thees and thous! That is the definition of not alone! Second, as a kid, nothing irked me more than getting told that something was a story for grown-ups, and that, everyone, is the story of how and why I read a number of books not at all appropriate for my age level. As a grown-up, that remembered irritation still colors my reading. If you have a story, Kipling, tell me. Don’t tell me it’s a story just for certain people.

Other editorial asides are equally annoying: “Now you must be content to skip ten or eleven whole years, and only guess at all the wonderful life Mowgli lived among the wolves….” No, Kipling, I’m NOT CONTENT. If it’s a wonderful life, let me hear about it. Don’t just tell me it would fill many books—that just makes me want it more.

The presentation of the Mowgli tales doesn’t really help either. For instance, the initial story, about Mowgli’s introduction to the wolf clan, ends with the haunting sentence:

The dawn was beginning to break when Mowgli went down the hillside alone, to meet those mysterious things that are called men.

Except that rather than getting this meeting, we get a poem and a story that functions as a flashback. It’s not a bad story, as it goes, but since I already know that Mowgli lives to the end of it, the attempt in the middle of the chapter to leave his fate in suspense is a failure from the get go.

The third story, however, gets back to the more interesting stuff: Mowgli’s meeting with men. It’s something that absolutely must happen, since Mowgli never quite manages to become fully part of the wolf world: he needs additional lessons from Baloo the bear just to understand the animal language, and the Laws of the Jungle, and even with a wolf family and two additional animal tutors, he still misses important lessons like “Never Trust Monkeys.” I summarize. But as the third tale demonstrates, Mowgli is not quite part of the human world, either: he has lived for far too long among wolves to understand humans and their customs, in an echo of Kipling’s own experiences.

Kipling, of course, had hardly invented the idea of a child raised by wolves or other animals—similar stories appear in folklore from around the world, often as origin tales for heroes or founders of great cities and empires, common enough that we’ll be encountering two such figures in this reread alone. But though couched in mythic language (which, I guess, partly explains those thees and thous), his take on these tales is slightly different. The stories are less interested in Mowgli’s strength and potential heroism, and more in discussing his position as outsider in nearly every culture: wolf, monkey, and human, with law, control, and allegiance as important subthemes. And they end on a somewhat ambiguous note: Mowgli chooses to leave humanity and return the jungle, to run with wolves, but the narrative immediately undercuts that, assuring us that eventually he returns to humanity. In other words, leaving us with a character still shifting between two worlds.

Other characters in the later stories are a bit more successful at finding their place in the world, and a home: the mongoose fights his way into a home and a place; the fur seal finds an island untouched by human hunters; the young boy earns a place among the elephant hunters. It’s probably important to note, however, that the mongoose needs to do this in part because he’s been displaced—he lost his home and parents through flooding. The fur seal, too, finds a home—but only after his fellow seals have been brutally slaughtered. The elephant overseers work under white overseers, in continuous danger of losing their homes. The animals brought to India to serve as mounts for the British army never do completely lose their uneasiness. Each tale offers an ambiguous, nuanced look at displacement from a writer who was all too familiar with this.

And now for a slightly less comfortable topic: The Jungle Book features many non-white characters along with animals. Not surprisingly for a 19th century book written by a British citizen who was to pen a poem titled “The White Man’s Burden,” however, Kipling does occasionally use some words that are or can be considered offensive towards these characters—most notably when describing the young Toomai as “looking like a goblin in the torch-light,” and in a later statement, “But, since native children have no nerves worth speaking of,” drawing a sharp divide between British and native children—in context, not in favor of the Indian children.

Kipling was certainly aware of and sensitive to racial distinctions in colonial India, and aware that many Indians strongly disagreed with British laws and regulations. This is even a subtheme of the final story, “Toomai of the Elephants,” which includes Indians criticizing British hunting practices: one Indian character openly calls the white character (his employer) a madman. The criticism seems deserved. The white character also tells jokes at the expense of his employees and their children, and although they laugh, their resentment is not that well concealed. The story also contains a later hint that the father of the main character, Toomai, does not want his son to come to the attention of white supervisors.

“Her Majesty’s Servants,” while focused more on the issues faced by horses and mules in the British Army, and which has a crack at the Amir of Afghanistan, also contains the sidenote that non-British elephant drivers weren’t paid on days where they were sick—something that does not happen with British cavalry officers, another stark disparity between the two groups. Kipling also includes the quiet note that in war, people and animals bleed, and in this war, led by British officers, native people are among those bleeding.

The Mowgli tales also contain multiple hints of racial conflicts, notably in the way that the jungle animals have created rules to help prevent further attacks and encroachments from invaders and colonists. Many of these rules frankly make no sense from a biological point of view, or even from the point of view of the animals in the story, but make absolute sense from the point of view of people attempting to avoid further subjugation. As do their efforts to cloak these rules in self-pride: the animals tell themselves that animals who hunt humans become mangy and lose their teeth, and that humans are too easily to kill anyway. But the real reason they don’t: they fear reprisals from humans if they do. It’s a legitimate fear, as the next stories show: Mowgli might have been raised by wolves, and he needs the assistance of his fellow pack members and a bear and a panther and a snake from time to time, but he is still superior.

A few other related points before we leave this: Kipling very much believes in the power of genetics over training. Mowgli, for instance, is skilled at woodwork not because anyone has taught him (until he heads to a human village, no one could), but because he’s the son of a woodworker. It’s strongly implied that Toomai is able to attend an elephant dance because his ancestors have always worked with elephants, creating an almost mystic bond, though it also helps that Toomai has basically been raised with elephants. And, well, the fur seal that just happens to lead all of the other little fur seals off to a safe island? Is a fur seal with pure white fur. This is not always a good thing for the fur seal, though it later helps to save his life, since the hunters think that a white seal is unlucky and decide not to kill him.

Given the rather large numbers of pure white harp seals killed then and now, this superstition seems, how can I put it, unlikely. Then again, my sense is that Kipling did not research fur seals or seal hunting in any great depth before writing his story—for instance, he briefly mentions that the Galapagos Islands are too hot for fur seals, apparently unaware of the Galapagos fur seals that haul out on those islands on a regular basis. It’s not, after all, really a story about seals, but rather, like the other tales here, a story about finding safety and home.

As universal as that theme might be, I can’t quite say that The Jungle Book is written from a universal, or even a non-British, point of view. But it’s also a book sharply aware that growing up, and changing worlds, is not always easy or safe, a book aware of inequities, and a book of quiet horrors, where the worst part may not be the scenes of stripping seals for fur.

Disney was to ignore almost all of this, as we’ll see next week.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

I found the fur seal story desperately sad – early on in the story, there’s a list of the types of seals that are killed by the hunters, and right at the end of the story, the seals go to the island in exactly the same order as that list, which led me to believe that there was no safety anywhere, and the seals were being killed despite the fur seal spending his life trying to find a safe place for them.

Harp seals live in the northern Atlantic while the story seems to take place in the Pacific. (Of course Kipling had the fliter feeding basking shark as a predator.)

I loved the Chuck Jones adaptations of the stories as a kid.

Also there is a stage version as well.

Kipling did indeed write another story about Mowgli becoming a man and marrying — quite apart from The Second Jungle Book, which I like almost as well as the First. “In the Rukh” (first published 1892) has a very different tone and sensibility from the later Jungle Book stories — it’s told from the POV of a white man to whom Mowgli appears almost as a forest fairy — and there are some queasy-making implications, so I can understand why Kipling labeled it a story for grown-ups and not children. All the same it’s a fascinating read.

I always understood the use of “thee” and “thou” to indicate that the characters were speaking an indigenous language; this is most apparent in Kim or in other works where characters slip from English to another language, changing diction and pronoun usage as they go. I still think it’s rather sad that English has lost its second person singular. though we seem to be making up for it in the other direction by an increased acceptance of “they” as a third person gender-neutral singular.

And Rikki-tikki-tavi has always been one of my heroes!

I’ve always found the penultimate Mowgli story, “Red Dog,” to be the most satisfying. It’s been pointed out that much of its power comes from its “classical” tropes and structure: there’s “society threatened by a barbarian horde,” “the suicidal exploit,” “the desperate fight in narrow place,” and “victory tempered by the death of the old leader.”

Even thinking about Akela’s death scene can get me choked up: “Howl, dogs! A wolf has died tonight!”

“Rikki-tikki-tavi” is one of the best “kid” stories I ever read when I was growing up, and I’ll be sure to read it to my kid pretty soon.

I read this when I was 6 or so–almost certainly my first fantasy, depending on how The Tales of Brare Rabbit is classified. So I had none of the problems our host had….Certainly the line about ‘a story for grownups’ didn’t bother me, ’cause every 6 yr. old knows stories about only humans & getting married is ‘Way More Boring than stories about being a young person in the jungle with a wolf pack. I still enjoy Kipling a lot.

It’s true hero figures raised by wolves/alpha predators are common to folklore, but it’s my understanding Kipling was basing this off several famous “wild boys” in India who were found outside villages & interested British scientists could not teach them to speak any language. Last I heard, it was speculated the “wild boys” were autistic children before autism was known. The “wild boys” were quite famous & may also have been the basis of ERB’s Tarzan.

I love the Jungle Books largely for their beautifully lyrical prose and poetry, and for having the most complex and personable set of “talking” animals I’ve met in a fantasy book aside from Redwall. “The Beaches of Lukannon,” the closing poem to “The White Seal,” is truly haunting, especially when sung by Gordon Bok.

The racism is clear, though. Non-whites are sometimes (though not always) cruel or backward, while whites are almost always benevolent. One of the worst stories for this, I think, is “The Undertakers.” It’s largely a fun scene of a jackal, a stork, and a crocodile chatting on the bank of an Indian river. But the croc boasts that the stupid local humans worship him even as he preys on them — though the pickings have been slimmer since pesky white men had a bridge built — and speaks of watching farmers kill each other over land newly created by river floods. He also says he once tried to bite off the hand of a little white boy — who then shows up, fully grown, to shoot him dead, to which local bystanders object. The after-poem is about a bride ceremonially entering the river despite knowing the danger, and getting eaten. The message: natives will keep getting themselves killed unless sensible whites step in to save them. White man’s burden, indeed.

Rikki-Tikki-Tavi is the story I re-read most from this book. That little mongoose is just great and please note that the female bird in this story is the smart one of the couple while the male bird mostly just sings his (admittedly funny, but meant seriously by him) songs.

Mary Beth- you beat me to In the Rukh, which is fine, because I couldn’t remember the title.

You could have devoted a post to each story and it would have been…productive. I discovered the 1st book at 9, the next a couple or 3 years on. They’ve resonated in various ways ever since.

First off, Bagheera didn’t need to hit Mowgli after the rescue from the monkeys; that kidnapping was punishment enough. Kaa did not need to insult Akela in “Red Dog”, and Mowgli’s tormenting the buffalo in the final story is out of character.

Always felt that Mowgli having to return to people was a letdown. The Spring Running was confusing and still remains a bit so. But vengeance–against the villagers, and the dholes–yes! Also being able to use one dangerous thing–the bees–against another.

“Aleuts are not clean people”–I lived in Ak. for some years, and of course they are the same mix of clean and dirty as the rest of us.

Good for Billy the mule for not passively putting up with an out-of the-blue anti-mule remark. That each species has its own strength is a nice touch, but there is the danger of making this too absolute, and limiting opportunities for growth, for some individual.

“The Undertakers”–even a crocodile has to spout sexist rage at having been shot by a female human. Contrast the loyalty between Mowgli and his “brothers” and mentors with the lack of any among the riverside trio. Also, that bit about proper jungle dwellers preferring aged meat. From what I know of Indian temperatures, it’s hard to imagine Mowgli having the same preferences…But I am still a big Kipling fan.

You might want to critique the Just So Stories and Pamela Jekel’s” Third Jungle Book”.

I’m sorry that you didn’t have anything to say about “The Miracle of Purun Bhagat”.

I was read these stories by my mother before I was old enough to read them for myself, and one of the things that I see that I got out of them, although I was unaware of it at the time, was that people from all sorts of different backgrounds were people, with their various strengths and weaknesses. Kipling’s non-white characters were well-developed and had their own idiosyncrasies when the story called for it. As a child, I didn’t come away from this book thinking that native peoples were inferior, just different from those that I lived among.

And I think that Mary Beth is correct about the language.

@10: When did a woman shoot the crocodile? I may be misremembering the.story. Agreed about the Jus So Stories, which I enjoy very much and would like to see on film.

@11: Wasn’t that admirable man’s wisdom and goodness partly attributed to his time learning from the British?

@12 I don’t think so – he attained high office under the Raj, and of course obtained a Western education while working in the colonial administration, but his essential quality as a person was due to his Indian background – he was called upon to spend a third of his life in public service, a third as a husband and father, and a third as a sanyassin, as I recall. Any virtues that he might have picked up from the British would have been of no relevance to his contemplative life, and he gave up all of the trappings of power to pursue it.

@10 The Aleuts Kipling was writing about were 19th Century Aleuts and didn’t have the access to hot water that modern Aleuts have. The individuals he describes also worked as sealers, which tends to get you filthy.

I thought that he deserved some credit in that story for describing the last of the Steller’s sea cows, although he didn’t call them that.

I know everyone is entitled to their opinion, but I really felt you didn’t do this book justice. The book I had contained only the Mowgli stories + the one about Rikki-tikki-tavi, so I cannot say anything about the other stories, but it was one of my favourite books growing up.

I think it contains many complex topics that are worth mentioning: brotherhood, the importance of family, how your environment shapes you, loyalty. I would rather disagree that Kipling believes genes are more important then the environment: Mowgli is very different than his wolf brothers, has his limitations (e.g. sense of smell) and his strengths (e.g. dexterity), but when it comes to the important things, he’s a wolf inside.Yes, at the end he goes to the humans, but I always thought this was in part because the jungle was different by that time: most of his friends were dead or very old and so he felt out of place. I always thought the last Spring run was a great representation of how growing up feels: you suddenly start seeing things in a different way, you feel as if you don’t belong, you are confused and angry because you are confused…

Ah, well, I guess I could talk about this book for hours and still have things to say.

@@.-@, yes the death of Akela always teared me up as well. Also, reading how Balu is getting old and weak…

Couldn’t disagree more about the thees and thous. One of the great strengths of the Jungle Book is the beauty of its language, I loved the strangeness and poetry of it as a child, and I think it works to elevate the talking animals above the realm of Disney. The animals are not in the story to be fun or cute, they are complex, dignified, sombre and strange characters in their own right, and the language reflects that.

The concept of Mowgli being alone despite his wolf companions is not an error either; it’s part of the theme. A part of Mowgli will always be alone among the wolves because of his human nature.

I have The Jungle Book and The Second Jungle Book collected as one, and find it much more satisfying as a whole story in this respect, since we do get the conclusion to Mowgli’s story. I think trying to fit the other non-Mowgli stories into the same thematic pattern doesn’t necessarily work though; Koatik and Rikki-Tikki et al deserve to be judged in their own right.

Randomly, it always annoyed me that Disney reversed the personalities of Baloo and Bagheera; in the book, Baloo is the strict, stuffy one and Bagheera is the “fun” parent who’d spoil Mowgli if he could.

“Bagheera is the “fun” parent who’d spoil Mowgli if he could.”

Very interesting, are Baloo and Bagheera male in the original text? In the translation I’ve read they are both female, both because the words “bear” and “panther” are feminine in Bulgarian and because names ending on vowels are generally considered female. I wonder how much this changed my perception of the book…

JAWolf – Kipling probably did have Pacific species in mind – he mentions the Galapagos specifically, and the focus is on fur seals, which for the most part live in the Pacific and Antarctic. However, Pacific harbor seals sometimes have white fur, and Kipling also would have seen coats and other garments made from the white fur of harp seals in England and Vermont. So I’m still not buying this.

Xena Catholica – It’s very possible that Kipling had the reports of “wild boys” in mind, reports that weren’t limited to India. One of the most famous cases was that of Peter the Wild Boy, found in 18th century Germany and brought to England. One

I’m going to slightly disagree with your comment about “everybody.” Can we make that “everybody but me”? Because The Jungle Book was read to me when I was about six, and yes, the “that is a story from grownups” bothered me even then. Like you, I wasn’t particularly into stories about kissing/getting married – that was all very boring – but I liked getting told that a story was only for grownups even less.

Angiportus – This Read-Watch is just focused on the specific Disney films. On the bright side, that saves you from multiple posts about The Rescuers books!

Salix Caprea – I expect you’re right that I didn’t completely do this book justice, but the problem is, although I can admire The Jungle Book for what it’s doing, I just don’t like it very much – quite possibly because I really didn’t like it when I was a kid, and those feelings continue to linger. But I don’t hate it either, which keeps me from really ripping it apart. I suspect we’re going to have similar problems with a few upcoming books that I don’t hate, but which left me cold (Treasure Island, for instance, which is excellent for what it does, and which I should love, because pirates, and pirates unafraid to do real pirating, and the truly great character of Long John Silver, but which I’ve never really been able to get into for whatever reason even with wondering what side Long John Silver will be on next.)

And yes, Baloo and Bagheera are both male in the original text. I had no idea they were female in the Bulgarian translation! Fascinating – and thanks for that!

@17 I seem to remember reading that Baloo was supposed to represent a “munshee,” a Hindu scholar/tutor, who was often stereotypically portrayed in fiction of the time as pedantic and humorless.

The crocodile tells his companions that way far back, a woman fired a few rounds at him, and one might still be under one of his scales. She was the mother of the child that he tried to grab from a boat, and who grew into the man that eventually shot him.

Hot baths were scarce for a lot of people in the 19th century, and there’s a difference tween doing work that makes one dirty and being generally unclean in one’s habits, the latter seeming to be what was implied in the seal story.

The Antarctic variety of fur seal sometimes produces white specimens. However I don’t know if these make it to adulthood, for all the images I’ve seen just show pups.

One comment that CS Lewis made on Rudyard Kipling focused on a line in one of his poems, which I’ve long since forgotten, but in relation to which CS Lewis said that Kipling was the poet of the man who does a job – not necessarily “the working man”, because Kipling was not a socialist any more than H Rider Haggard was. Even Mowgli gets drafted into the Indian Civil Service …

Another Kipling book that deserves a mention: Captains Courageous. It is one of the best coming-of-age books I’ve read.

Of course, Kipling with his strident Imperialism left himself wide open to attack: CS Lewis makes his phrase “White Man’s Burden” the touchstone of arrogant imbecility in Out Of the Silent Planet. And Kipling gets enverbed in Gallipoli, when one of the characters recites one of his poems then asks one of the random characters if he likes Kipling. “I’ve never kippled” is the reply he gets.

Kim gets drafted into the Indian Civil Service; I don’t think Mowgli does.

Mowgli does end up working as a forest-guard for the Department of Woods and Forest in “In the Rukh,” with a monthly salary in silver (and a pension). I wouldn’t say he’s drafted, though; he’s offered the job twice, spends the day thinking it over, and then sets his own terms and conditions.

The story is available online: http://www.telelib.com/authors/K/KiplingRudyard/prose/ManyInventions/rukh.html

I grew up about an hour from Disney and still love the movies. So I have really enjoyed this Read Watch, and was really looking forward to this post specifically, but it was disappointing. Almost as disappointing as the Disney movie they made based on this book :)

I didn’t understand a lot of the objections outlined here (specifically related to the Mowgli stories, as I’ve only read Part II a few times and probably not for 10 years). The presentation for instance – well it’s not a novel. So he tells one whole story that focuses on Mowgli’s relationship with the wolves, which ends when Mowgli goes to the man village because after that, his relationship with them changes. If it were a novel, sure, you’d want the man village part to come next. But since it’s a short story collection, they’re a bit out of order – he tells something that happened concurrent with the first story second, and then tells a story that happens later (Mowgli in the village).

I also don’t mind that he didn’t tell us ALL about Mowgli’s life, instead focusing on a few key things and hinting that his other adventures were great too. This is a children’s book, after all, and it’s good to encourage imagination. To me, there’s nothing wrong with hinting and not showing.

Others have commented on the language and I agree. I guess you either like it or you don’t. But I’ve also read Kim several times and this to me is just Kipling’s style, which I personally like.

Lastly, I’m sorry but I have no idea what this means: “The Mowgli tales also contain multiple hints of racial conflicts, notably in the way that the jungle animals have created rules to help prevent further attacks and encroachments from invaders and colonists. Many of these rules frankly make no sense from a biological point of view, or even from the point of view of the animals in the story, but make absolute sense from the point of view of people attempting to avoid further subjugation.” Huh? Are there other examples than the not eating man one you cite, which the book DOES explain from the animal’s POV as being sensible because they ultimately fear retaliation and being hunted as dangerous man-eaters? I thought that was clear and never did/still don’t read racial subtext into it.

Thanks for your musings, Mari. I’ve never read this so I guess I don’t have much to add. I enjoy the movie but always knew it was only very loosely based on the book.

Isn’t this one of The Jungle Book’s great strengths, though? Mowgli is non-white, and he’s smart and resourceful and a generation of children grew up wanting to be him. And yet you didn’t mention him, when you listed the Jungle Books’ treatment of race – and I’m guessing that’s because Mowgli’s race is irrelevant to the story, as it should be.

I think Kipling deserves a hell of a lot of credit for writing two best-selling books about a brown kid, and for doing so before the close of the 19th century. And I think he deserves even more credit for not making the books about race. What he draws your attention to – what sets Mowgli apart and makes him special – is not that Mowgli is brown but that Mowgli is human.